*Guns were sometimes drawn, but I didn’t really think it mattered where it went down. I also had a loaded 9-mill Mauser tucked under my pillow - as far as I was concerned, if anyone came in here uninvited, I’d let the Mauser do the talking. *

This was how Niilo Ranttila, the maker of a gold strike on the Lemmenjoki River, described the first years of the gold rush at the turn of the 1940s and 1950s.

IRanttila, who lived on the Inarijoki River, had gone to Lemmenjoki with his brothers Uula and Veiko in the last weeks of August in 1945 to prospect for gold. In the beginning, the three brothers explored the areas around the Vaijoki and Nihasanjoki rivers, as it had been reported that gold had been found at Lemmenjoki. But they found nothing.

In mid-September, the brothers went up the Morgamoja River and Niilo made a test hole on the banks of a stream. Upon finding a yellowish stone crumb there, Niilo bit into it to confirm his finding. He had put his teeth marks into a three gram nugget of gold. They had found the Lemmenjoki gold.

First gold rush ended in betrayal and disappointment

However, the story of Lemmenjoki gold begins just under a hundred years earlier. In 1867, Konrad Wilhelm Planting, a Crown official for the district of Lapland, sent a letter to the Department of Northern Mining Affairs. In the letter, Planting, who was interested in geology, presented his own views on the gold in Lapland and proposed studying the waterways of the Tana, Inarijoki, Kietsimäjoki, Vaskojoki, Lemmenjoki, Menesjoki, Repojoki, Luttojoki and Ivalojoki rivers.

Planting’s letter presaged the first gold rush in Lapland, which began in 1870. However, this was almost exclusively concentrated in the Ivalojoki River, where Oulu residents Jakob Ervasti and Nils Lepistö had struck gold in the summer of 1869. Inspired by this news, 500 gold prospectors made their way to the Ivalojoki River the following summer to try their luck.

Only one gold prospecting claim at Lemmenjoki made good on its promise. The strike was made by Henrik Tallgren, an engineer captain from Helsinki, but the gold was not found on the Lemmenjoki River. It was assumed that Lemmenjoki gold lies deeper inside the earth than the gold found in the Ivalojoki River at that time.

Individual gold prospectors worked along Lemmenjoki throughout the late 19th century, but their takings remained rather meagre. However, Kaarle Gummerrus of Revonlahti started a rumour of the gold he had found in the Puskuoja River. For a fee, Gummerrus offered to guide anyone excited about his rumoured gold strike to the Puskuoja River, where he showed them his prospecting pits. Even though no gold had been found in the Puskuoja River, Gummerrus still made off with his guide fees. At the turn of the 19th century, he was the only prospector to strike it rich on Lemmenjoki gold.

The gold rush soon died out and all of the prospectors left the river valley.

The new gold rush fulfilled dreams, brought bitter disappointment and gave birth to the Gold Prospectors' Association of Finnish Lapland

The next gold rush began after the Second World War with the gold strike made by Niilo Ranttila. Five years after Ranttila’s first strike, gold was found in Lemmenjoki on nearly a hundred claims.

Gold was also found on many claims by the kilogram, while others were left without a single crumb. This made life in the goldfields wild and restless, as is evident in the description given by Ranttila above.

At that time, many of the gold prospectors were war veterans, whose scars still showed. After years of war in the wilderness, finding one's own place in civil society may have proved difficult. The goldfields of the fells provided them with a safe haven to spend their lives. However, the threshold for violence may have been low. For example, Jukka Pellinen, the co-chairman of the Gold Prospectors' Association of Finnish Lapland established in Lemmenjoki, was killed in a gunfight.

Indeed, the Gold Prospectors' Association of Finnish Lapland was established in 1949 to resolve conflicts between prospectors. It also became an important trustee for gold prospectors. For example, the Association was instrumental in significantly improving transport connections to Lemmenjoki. It managed to arrange a regular boat service, which continues to this day, cleared land for two airfields for the transport of goods and food, and provided funding for a citizen delegation lobbying for the Njurkulahti road.

Goldfields fall silent, lifers remain

Despite the establishment of an association and flurry of civic activities in the 1950s, the goldfields of the Lemmenjoki River began fall silent at the end of the decade. This development was typical of all the earlier gold rushes. They ran out of steam when, after the initial fever of the rush, not enough gold was found for everyone, and prospectors began to lose faith in the possibility of ever striking gold.

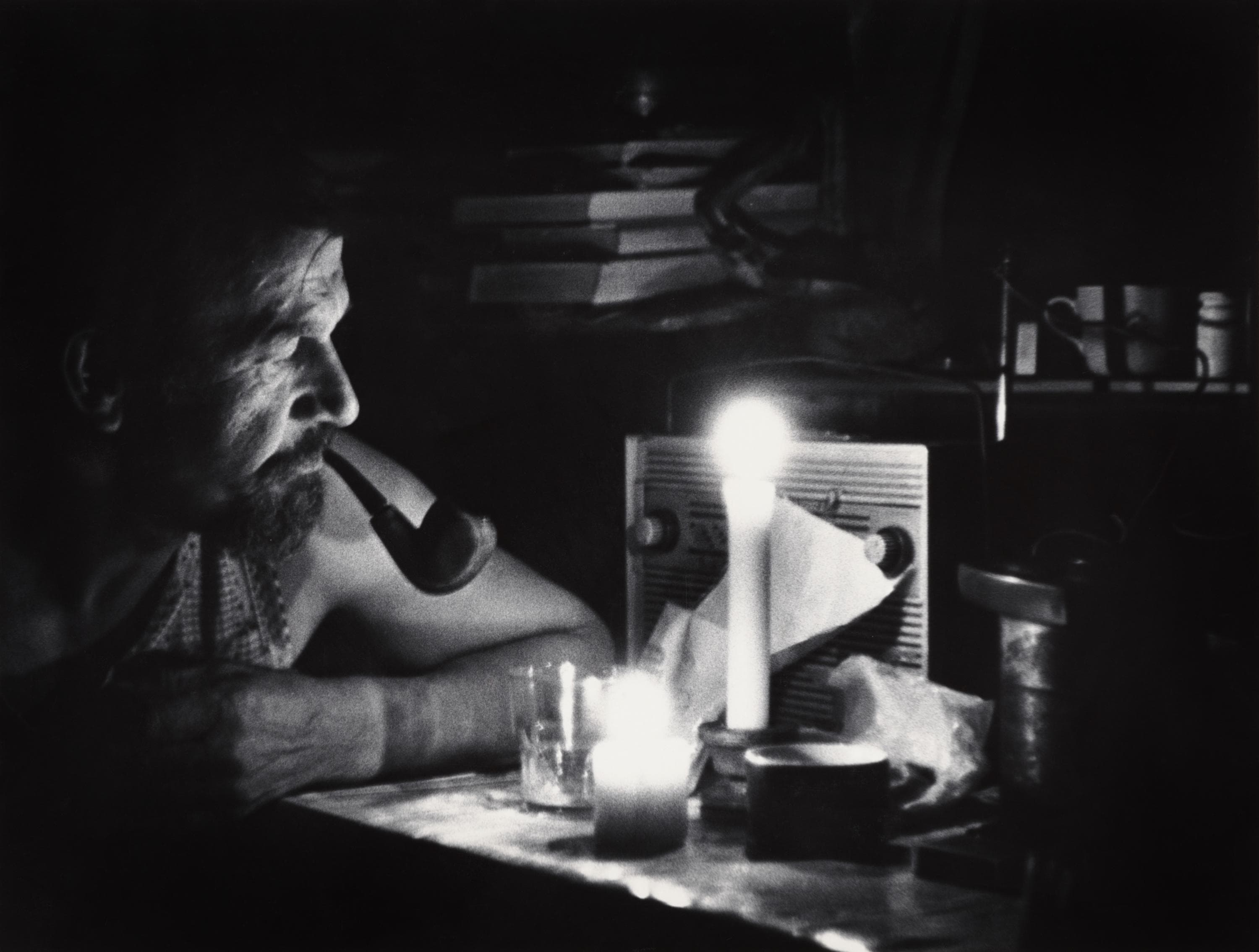

However, a new phenomenon occurred at Lemmenjoki when some of the prospectors stayed on, becoming known as ‘lifers’. They lived a quiet life, spending the summer digging for gold and almost going into hibernation in their cottages in the winter.

At the beginning of the 1960s, there were only seven claims at Lemmenjoki. In the summer, prospectors, sometimes in large numbers, might try their luck in the goldfields, and the occasional hiker might pass through. It was during these times that the lifers enjoyed quite a busy social life. On the flip side, they might not see another soul for months on end in the winter. Living this kind of life demanded a sound mind and inner peace.

It was the era of these lifers that gave rise to many of the legends about gold prospectors on the Lemmenjoki River. Living on a claim all year round required a sound mind and the ability to live in harmony with oneself.

A new enthusiasm and the breakthrough of machine prospecting

Most of the lifers moved on to more lucrative goldfields in the 1970s and 1980s, but many of them were still around to see a new boom in gold prospecting in Lemmenjoki.

This boom was driven by a new enthusiasm for gold prospecting in the 1970s. For example, the highly popular Finnish Open Gold Panning Championships began at Tankavaara. This new enthusiasm also spread to Lemmenjoki.

The new gold rush in Lemmenjoki began to take shape in the 1980s and peaked in the 1990s. This growth is especially evident, for example, in the number of members in the Gold Prospectors' Association of Finnish Lapland, which was 328 in 1980. In 2002, the number of members had already increased to 1,500.

At the same time, gold prospecting on the Lemmenjoki River underwent a major change with the advent of machine prospecting. Mechanical prospecting, with its new technologies, enabled prospectors to process many times the amount of soil profitably. Indeed, many prospectors started making a living from gold.

The mechanisation of prospecting also ran into conflicts with nature conservation. Machine prospectors and nature conservationists first faced off with each other at the Sotajoki River, but a ban on mechanical prospecting was soon imposed at Lemmenjoki. Mechanical prospecting was banned in the national park framework plan, which was completed in 1988.

This was followed by a long dispute in the courts, eventually resulting in the ban on mechanical prospecting remaining in force. However, mechanical prospecting could still be practised on claims where the prospecting was already underway. At the same time, claims became mining concession areas.

The new Mining Act entered into force in 2011, officially banning mechanical prospecting in Lemmenjoki after a transition period. The machines fell silent in the goldfields in the summer of 2020, but traditional shovel prospecting continues.

The song of gold, dreams, faith, bedrock, life-changing strikes and bitter disappointments on the Lemmenjoki River still goes on.